DESCARGAR

VERSIÓN

ARTÍCULO

DESCARGAR

VERSIÓN

EXTENSA

DESCARGAR

ANEXOS

DESCARGAR

VERSIÓN

CORTA

DESCARGAR RECOMENDACIONES Y FLUJOGRAMAS

vacio

vacio

Ámbito

- Esta guía debe ser usada en todos los establecimientos del seguro social del Perú (EsSalud), según lo correspondiente a su nivel de atención.

Población y alcance

- Población: pacientes con leucemia linfoblástica aguda.

- Alcance: manejo inicial de leucemia linfoblástica aguda.

Autores

Expertos clínicos:

-

Moreno Larrea Mariela del Carmen

-

Pizarro Perea Marlies Gyssel

-

Rojas Soto Ninoska Julia

-

Aranda Gomero Lourdes María del Pilar

-

Arteta Altamirano Cecilia

-

Eyzaguirre Zapata Renee Mercedes

Metodólogos:

-

Goicochea Lugo Sergio

-

Nieto Gutiérrez Wendy

-

Taype Rondán Alvaro

Coordinadores:

-

Timaná Ruiz Raúl

Descargar PDF con más información sobre la filiación y rol de los autores.

Metodología

Resumen de la metodología:

- Conformación del GEG: La Dirección de Guías de Práctica Clínica, Farmacovigilancia y Tecnovigilancia, del Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación (IETSI) del Seguro Social del Perú (EsSalud), conformó un grupo elaborador de la guía (GEG), que incluyó médicos especialistas y metodólogos.

- Planteamiento de preguntas clínicas: En concordancia con los objetivos y alcances de esta GPC, se formularon las preguntas clínicas.

- Búsqueda de la evidencia para cada pregunta: Para cada pregunta clínica, se realizaron búsquedas de revisiones sistemáticas (publicadas como artículos científicos o guías de práctica clínica). De no encontrar revisiones de calidad, se buscaron estudios primarios, cuyo riesgo de sesgo fue evaluado usando herramientas estandarizadas.

- Evaluación de la certeza de la evidencia: Para graduar la certeza de la evidencia, se siguió la metodología Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE), y se usaron tablas de Summary of Findings (SoF).

- Formulación de las recomendaciones: El GEG revisó la evidencia recolectada para cada una de las preguntas clínicas en reuniones periódicas, en las que formuló las recomendaciones usando la metodología GRADE, otorgándole una fuerza a cada una. Para ello, se tuvo en consideración los beneficios y daños de las opciones, valores y preferencias de los pacientes, aceptabilidad, factibilidad, equidad y uso de recursos. Estos criterios fueron presentados y discutidos, tomando una decisión por consenso o mayoría simple. Asimismo, el GEG emitió puntos de buenas prácticas clínicas (BPC) sin una evaluación formal de la evidencia, y mayormente en base a su experiencia clínica.

- Revisión externa: La presente GPC fue revisada en reuniones con profesionales representantes de otras instituciones, tomadores de decisiones, y expertos externos.

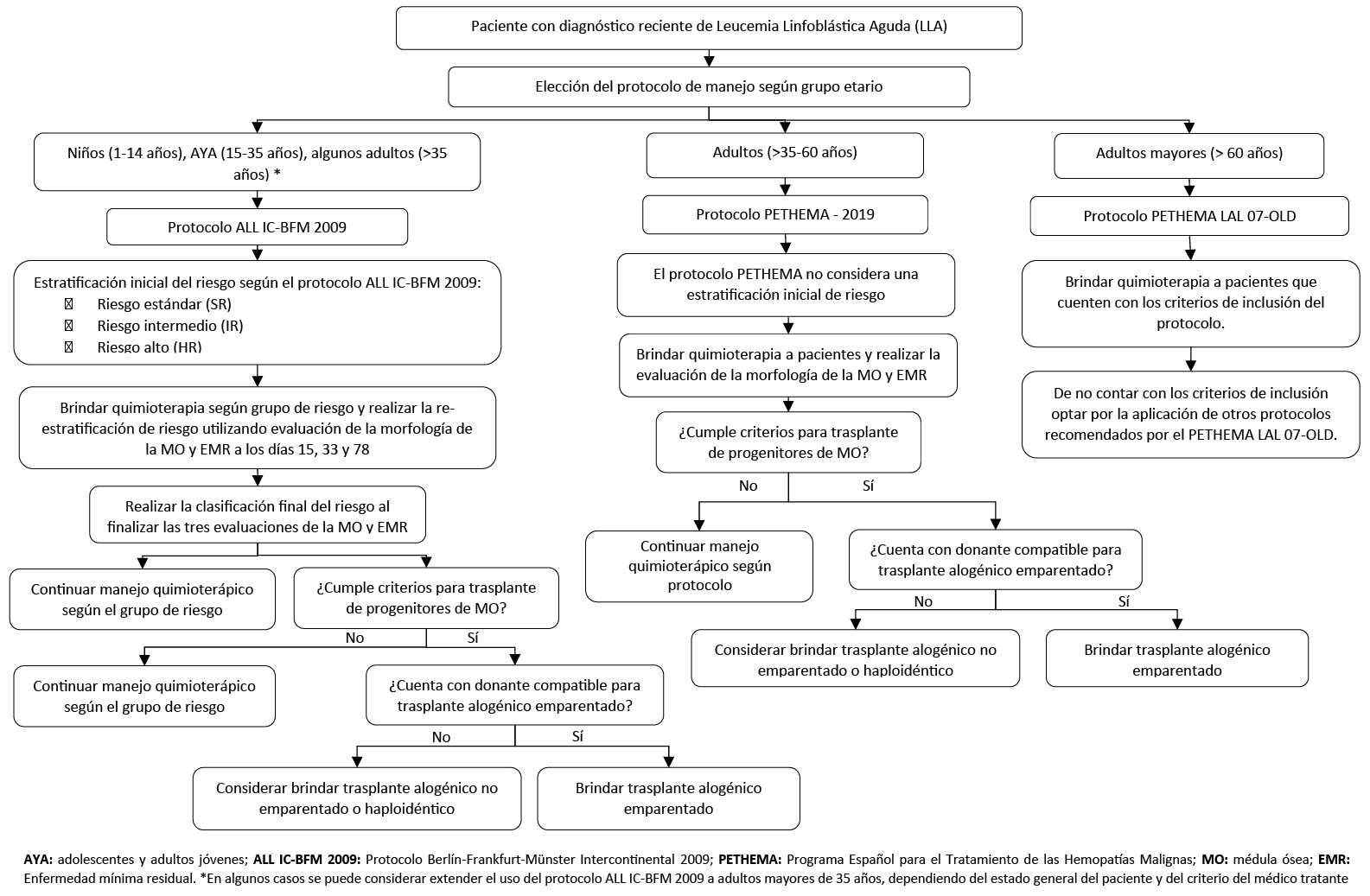

Flujogramas que resumen el contenido de la GPC

vacio

vacio

1. Protocolo de manejo para niños

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

BPC 1:

En niños (1 a 14 años) con LLA, utilizar el protocolo Berlín-Frankfurt-Münster Intercontinental 2009 (ALL IC-BFM 2009) para el manejo quimioterapéutico de esta neoplasia.

BPC 2:

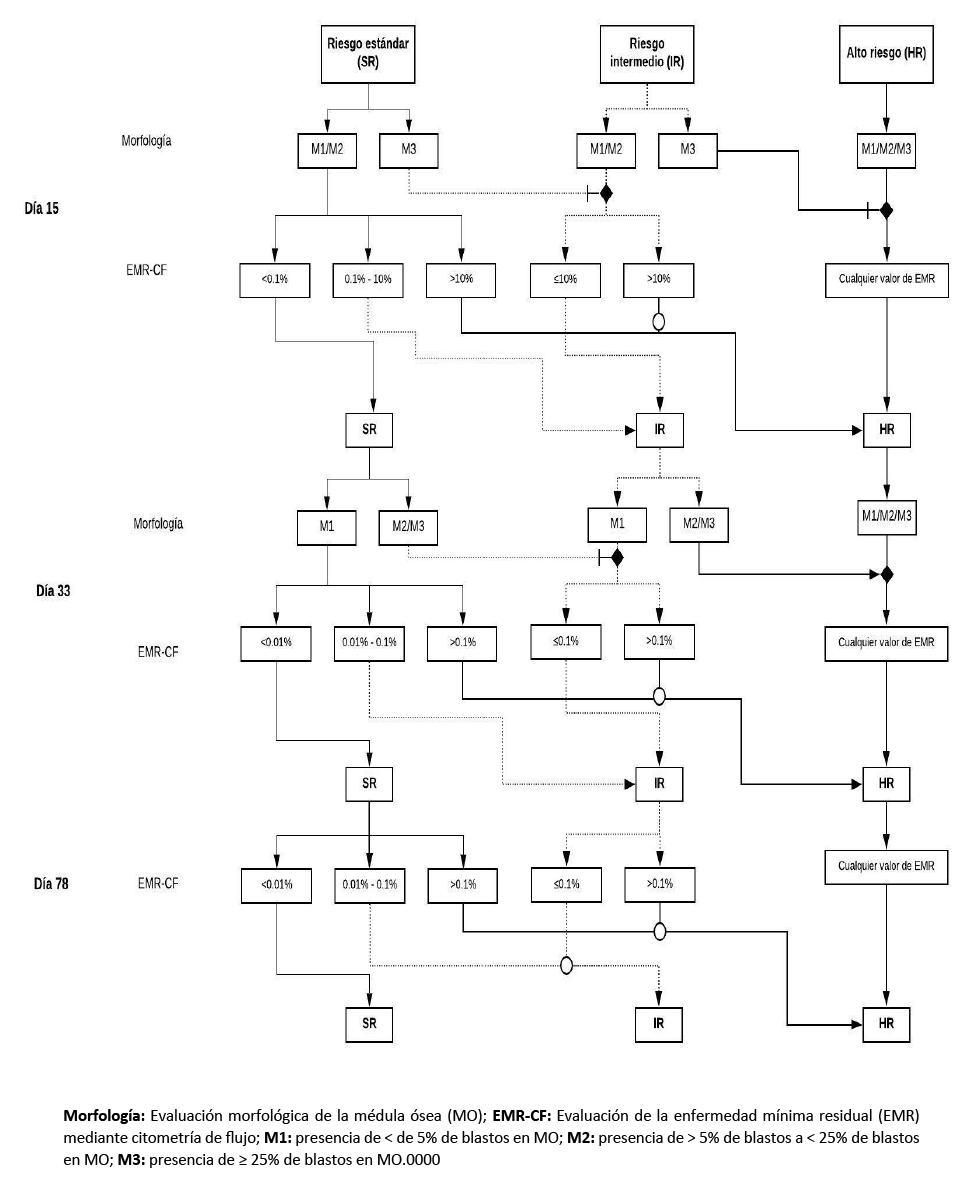

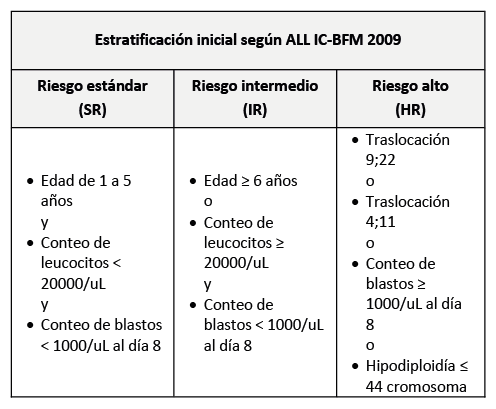

En niños (1 a 14 años) con LLA, respecto a la estratificación de riesgo de los pacientes:

- Realizar a estratificación inicial de riesgo utilizando los criterios del protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009.

- Re-estratificar el riesgo durante el transcurso de la quimioterapia utilizando la evaluación de la Enfermedad Mínima Residual (EMR), según el protocolo Italian Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Berlín-Frankfurt-Münster 2009 (AIEOP-BFM 2009).

- Se definirá EMR positiva con los siguientes puntos de corte en los días 15, 33 y 78 de haber iniciado el manejo:

- Utilizar los siguientes valores de EMR en los días 15, 33 y 78 de haber iniciado para re-estratificar el grupo de riesgo:

BPC 3:

En niños (1 a 14 años) con LLA, evaluar la EMR utilizando el método de citometría de flujo.

BPC 4:

En niños (1 a 14 años) con LLA, utilizar las indicaciones de trasplante de precursores hematopoyéticos de médula ósea basados en los protocolos ALL IC-BFM 2009 y AIEOP-BFM 2009:

2. Protocolo de manejo para adolescentes y adultos jóvenes

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En adolescentes y adultos jóvenes (15 a 35 años) con LLA, recomendamos utilizar un protocolo “pediátrico” en vez de un protocolo “para adultos” para el manejo quimioterapéutico de esta neoplasia. (Recomendación fuerte a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

BPC 1:

En adolescentes y adultos jóvenes (15 a 35 años) con LLA, utilizar el protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009 para el manejo quimioterapéutico de esta neoplasia.

BPC 2:

En adolescentes y adultos jóvenes (15 a 35 años) con LLA, respecto a la estratificación de los pacientes, seguir los puntos de buena práctica clínica propuestos para el manejo de niños (1 a 14 años).

BPC 3:

En adolescentes y adultos jóvenes (15 a 35 años) con LLA, evaluar la EMR utilizando el método de citometría de flujo.

BPC 4:

En adolescentes y adultos jóvenes (15 a 35 años) con LLA, utilizar las indicaciones de trasplante de precursores hematopoyéticos de médula ósea basados en los protocolos ALL IC-BFM 2009 y AIEOP-BFM 2009, mencionados en como punto de buena práctica clínica para el manejo de niños (1 a 14 años).

BPC 5:

En algunos casos particulares, considerar extender el uso del protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009 a adultos de 35 a 40 años con LLA dependiendo del estado general del paciente y del criterio del médico tratante.

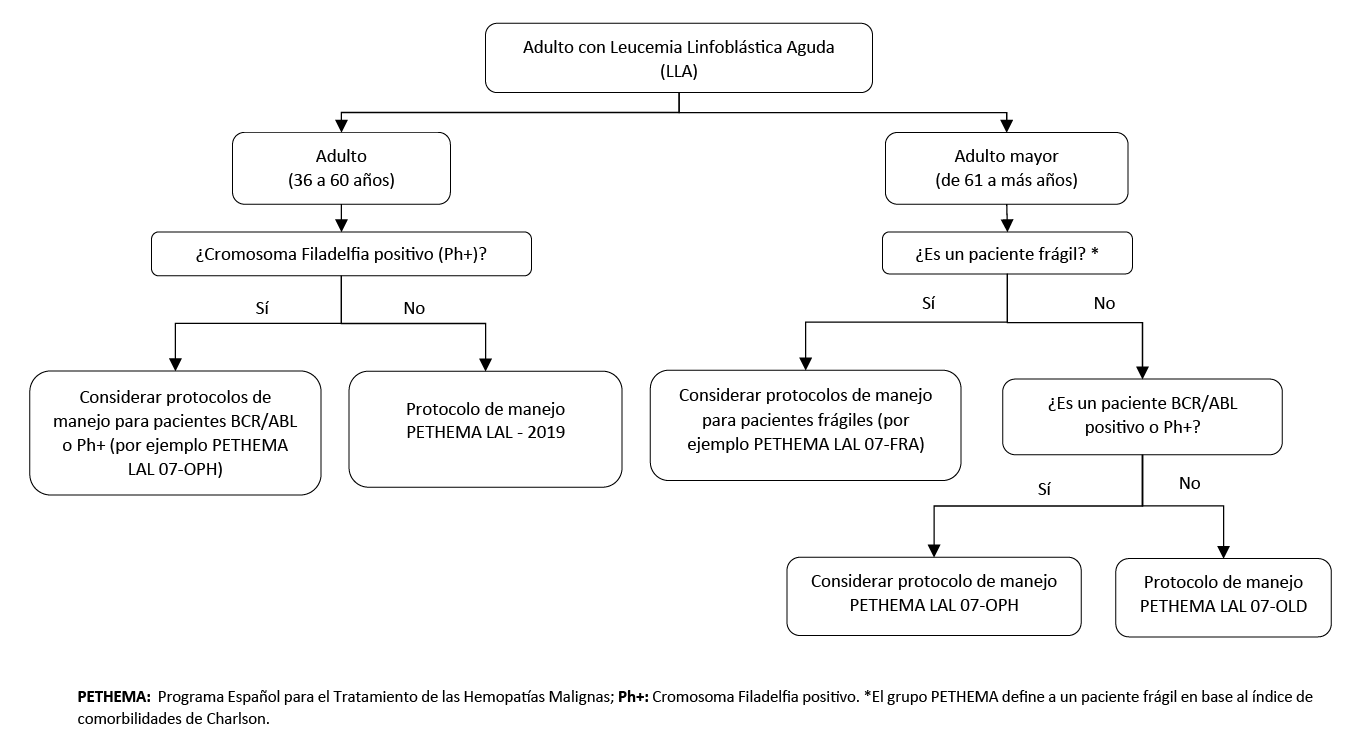

3. Protocolo de manejo para adultos

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

BCP 1:

En adultos (36 a 60 años) con LLA, utilizar el protocolo del Programa Español para el Tratamiento de las Hemopatías Malignas (PETHEMA) con código de protocolo LAL – 19 para el manejo quimioterápico de esta neoplasia.

BCP 2:

En adultos (36 a 60 años) con LLA, respecto a la evaluación de la EMR:

- Utilizar los puntos de corte propuestos por el protocolo PETHEMA LAL – 2019 para decidir la conducta terapéutica a brindar de la siguiente manera:

- Evaluar la EMR utilizando el método de citometría de flujo.

BCP 3:

En adultos (36 a 60 años) con LLA, utilizar las indicaciones de trasplante de precursores hematopoyéticos de médula ósea del protocolo PETHEMA LAL – 2019.

BCP 4:

En adultos mayores (61 años a más) con LLA que sean considerados candidatos para el manejo quimioterapéutico, utilizar el protocolo del Programa Español para el Tratamiento de Leucemia Linfoblástica Aguda con cromosoma Filadelfia negativo en pacientes de edad avanzada (PETHEMA) LAL 07-OLD para el manejo de esta neoplasia.

4. Primera punción lumbar

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

BPC 1:

En pacientes con LLA sin síntomas neurológicos sugestivos de infiltración, realizar la primera punción lumbar para evaluar la infiltración al sistema nervioso central (SNC) y brindar la primera terapia intratecal entre los días uno al siete luego de haber iniciado la prefase con prednisona. Posteriormente, en caso de no encontrar infiltración al SNC, las restantes Terapias Intra Tecales (TIT) profilácticas se realizarán los días 15 y 33.

BPC 2:

En pacientes con LLA con síntomas neurológicos sugestivos de infiltración, realizar la primera punción lumbar para el diagnóstico de infiltración al sistema nervioso central el primer día en que se inicia la prefase con prednisona.

5. Protocolo IB de intensidad aumentada

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes de 1 a 14 años con LLA de riesgo intermedio o alto que se encuentren en fase de consolidación temprana con el protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009, sugerimos utilizar el protocolo IB de intensidad estándar en vez del protocolo IB de intensidad aumentada (Recomendación condicional a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

Recomendación 2:

En pacientes de 15 a más años con LLA de riesgo intermedio o alto que se encuentren en fase de consolidación temprana con el protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009, recomendamos utilizar el protocolo IB de régimen estándar en vez del protocolo de régimen aumentado. (Recomendación fuerte a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

6. Dosis de metotrexato

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

BPC 1:

En pacientes con LLA de linaje B con riesgo intermedio que se encuentren en fase de consolidación con el protocolo ALL IC-BFM 2009, administrar 5000 mg/m2 de metrotexato.

BPC 2:

En los pacientes con LLA que reciban dosis altas de metotrexato, se debería realizar el dosaje de los niveles plasmáticos de metotrexato con el fin de monitorear concentraciones óptimas y/o tóxicas del fármaco.

7. Uso de inhibidores de la Tirosina-Cinasa en Ph+

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes de 1 a 18 años con LLA y Ph+, recomendamos administrar el TKI Imatinib desde la confirmación de la presencia de Ph+. (Recomendación fuerte a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

BCP 1:

En pacientes de 1 a 18 años con LLA y Ph+, administrar Imatinib a dosis de 340 mg/m2/ día por vía oral de manera conjunta a la quimioterapia.

BCP 2:

En pacientes de 18 a más años con LLA y Ph+, administrar Imatinib a dosis de 600 a 800 mg/día por vía oral de manera conjunta a la quimioterapia.

8. Trasplante

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes con LLA en remisión completa candidatos a trasplante de progenitores hematopoyéticos en los que no se encuentra disponible el trasplante alogénico emparentado idéntico, sugerimos brindar trasplante alogénico haploidéntico o no emparentado teniendo en cuenta la condición clínica, el balance de riesgo y beneficios para cada paciente, y la disponibilidad de recursos logísticos. (Recomendación condicional a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

BCP 1:

En pacientes con LLA en remisión completa candidatos a trasplante de progenitores hematopoyéticos, en los que no se encuentra disponible el trasplante alogénico emparentado idéntico, el esquema de acondicionamiento previo al trasplante (mieloablativo o de intensidad reducida) dependerá de la condición clínica del paciente y el criterio del médico tratante.

BCP 2:

En pacientes con LLA en remisión completa candidatos a trasplante de progenitores hematopoyéticos, en los que no se encuentra disponible el trasplante alogénico emparentado idéntico, brindar ciclofosfamida a dosis de 50 mg/kg/día durante dos días para la depleción de células T posterior al trasplante.

Referencias bibliográficas

- WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, revised 4th edition, Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. (Eds), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon 2017. 2017.

- Dores GM, Devesa SS, Curtis RE, Linet MS, Morton LM. Acute leukemia incidence and patient survival among children and adults in the United States, 2001-2007. Blood. 2012;119(1):34-43.

- Redaelli A, Laskin B, Stephens J, Botteman M, Pashos C. A systematic literature review of the clinical and epidemiological burden of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL). European journal of cancer care. 2005;14(1):53-62.

- Dirección General de Epidemiología, Ministerio de Salud. Boletín Epidemiológico (Lima). Del 03 al 09 de agosto del 2014. Volumen 23-Semana epidemiológica N° 32 [Internet]. Lima: MINSA; 2014. Disponible en http://www. dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2014/32.pdf.

- Santillan GAH, Zapata RE, Zuloeta JS. Neutropenia febril posterior a quimioterapia de consolidación en pacientes pediátricos con leucemia linfoblástica aguda del Hospital Nacional Guillermo Almenara Irigoyen durante 2008-2010. Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo. 2011;4(2):99-102.

- TELLO-VERA S, COLCHADO-AGUILAR J, CARPIO-VÁSQUEZ W, RODRÍGUEZ-GUEORGUIEV N, DÍAZ-VÉLEZ C. Supervivencia de pacientes con leucemias agudas en dos hospitales de la seguridad social del Perú. Revista Venezolana de Oncología. 2018;30(1):2-9.

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2010;182(18):E839-E42.

- Ministerio de Salud. Documento técnico: Metodología para la de documento técnico elaboración guías de practica clínica. Lima, Perú: MINSA; 2015.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj. 2017;358:j4008.

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. Bmj. 2011;343:d5928.

- Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919.

- Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2013;66(7):726-35.

- Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2013;66(7):719-25.

- Chiaretti S, Jabbour E, Hoelzer D. «Society of Hematologic Oncology (SOHO) State of the Art Updates and Next Questions»-Treatment of ALL. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia. 2018;18(5):301-10.

- Pui C-H, Evans WE. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(2):166-78.

- National Cancer Institute [Internet]. NIH: USA [citado 12 marzo 2019] NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms [Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/bone-marrow-transplant.

- Hunger SP, Mullighan CG. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(16):1541-52.

- Hunger SP, Lu X, Devidas M, Camitta BM, Gaynon PS, Winick NJ, et al. Improved survival for children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia between 1990 and 2005: a report from the children’s oncology group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30(14):1663-9.

- Schrappe M, Valsecchi MG, Bartram CR, Schrauder A, Panzer-Grumayer R, Moricke A, et al. Late MRD response determines relapse risk overall and in subsets of childhood T-cell ALL: results of the AIEOP-BFM-ALL 2000 study. Blood. 2011;118(8):2077-84.

- Conter V, Bartram CR, Valsecchi MG, Schrauder A, Panzer-Grumayer R, Moricke A, et al. Molecular response to treatment redefines all prognostic factors in children and adolescents with B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results in 3184 patients of the AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000 study. Blood. 2010;115(16):3206-14.

- Stary J, Zimmermann M, Campbell M, Castillo L, Dibar E, Donska S, et al. Intensive chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of the randomized intercontinental trial ALL IC-BFM 2002. Journal of clinical oncology. 2013;32(3):174-84.

- Schrappe M ea. ALL IC-BFM 2009: A Randomized Trial of the I-BFM-SG for the Management of Childhood non-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia 2010 [Available from: http://www.bialaczka.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/ALLIC_BFM_2009.pdf.

- Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Reiter A, Henze G, Schrauder A, Gadner H, et al. Long-term results of five consecutive trials in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia performed by the ALL-BFM study group from 1981 to 2000. Leukemia. 2010;24(2):265.

- Basso G, Veltroni M, Valsecchi MG, Dworzak MN, Ratei R, Silvestri D, et al. Risk of relapse of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia is predicted by flow cytometric measurement of residual disease on day 15 bone marrow. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(31):5168-74.

- Berry DA, Zhou S, Higley H, Mukundan L, Fu S, Reaman GH, et al. Association of Minimal Residual Disease With Clinical Outcome in Pediatric and Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Meta-analysis. JAMA oncology. 2017;3(7):e170580.

- Van der Velden V, Panzer-Grümayer E, Cazzaniga G, Flohr T, Sutton R, Schrauder A, et al. Optimization of PCR-based minimal residual disease diagnostics for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a multi-center setting. Leukemia. 2007;21(4):706.

- Conter V, Schrauder A, Gadner H, Valsecchi MG, Zimmermann M, Dvorzak M, et al. Impact of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) on Prognosis in Children with Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) According to WBC Count, Age and TEL/AML1 Status at Diagnosis. Results of the AIEOP-BFM ALL 2000 Study. Am Soc Hematology; 2007.

- Campana D. Minimal residual disease in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2010;2010:7-12.

- Schafer ES, Hunger SP. Optimal therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2011;8(7):417.

- Curran E, Stock W. How I treat: acute lymphoblastic leukemia in older adolescents and young adults (AYAs). Blood. 2015:blood-2014-11-551481.

- Ram R, Wolach O, Vidal L, Gafter-Gvili A, Shpilberg O, Raanani P. Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia have a better outcome when treated with pediatric-inspired regimens: systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of hematology. 2012;87(5):472-8.

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social. Guía de Práctica Clínica para la detección, tratamiento y seguimiento de leucemias linfoblástica y mieloide en población mayor de 18 años. In: Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud, editor. Bogotá, Colombia: MINSALUD; 2017.

- Sawalha Y, Advani AS. Management of older adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: challenges & current approaches. International journal of hematologic oncology. 2018;7(1):IJH02-IJH.

- Shin D-Y, Kim I, Kim K-H, Choi Y, Beom SH, Yang Y, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in elderly patients: a single institution’s experience. The Korean journal of internal medicine. 2011;26(3):328-39.

- Taylor PR, Reid MM, Bown N, Hamilton PJ, Proctor SJ. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in patients aged 60 years and over: a population-based study of incidence and outcome. Blood. 1992;80(7):1813-7.

- Gökbuget N. Treatment of older patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology American Society of Hematology Education Program. 2016;2016(1):573-9.

- Lamanna N, Heffner LT, Kalaycio M, Schiller G, Coutre S, Moore J, et al. Treatment of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: do the specifics of the regimen matter?: Results from a prospective randomized trial. Cancer. 2013;119(6):1186-94.

- Gökbuget N, Hoelzer D, editors. Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Seminars in hematology; 2009: Elsevier.

- Ribera J-M, Morgades M, Ciudad J, Montesinos P, Barba P, García-Cadenas I, et al. Post-Remission Treatment with Chemotherapy or Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (alloHSCT) in Adult Patients with High-Risk (HR) Philadelphia Chromosome-Negative (Ph-neg) Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) According to Their Minimal Residual Disease (MRD). Final Results of the Pethema ALL-HR-11 Trial. American Society of Hematology Washington, DC; 2019.

- Asociación española de hematología y hemoterapia. Programa Español para el tratamiento de las hemopatias malignas (PETHEMA): Protocolo para el tratamiento de la Leucemia Aguda Linfoblástica BCR/ABL negativa en adultos: LAL-2019. 2019.

- Spath-Schwalbe E, Heil G, Heimpel H. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in patients over 59 years of age. Experience in a single center over a 10-year period. Annals of hematology. 1994;69(6):291-6.

- Sancho JM, Ribera JM, Xicoy B, Morgades M, Oriol A, Tormo M, et al. Results of the PETHEMA ALL-96 trial in elderly patients with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. European journal of haematology. 2007;78(2):102-10.

- Larson RA, Dodge RK, Linker CA, Stone RM, Powell BL, Lee EJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of filgrastim during remission induction and consolidation chemotherapy for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: CALGB study 9111. Blood. 1998;92(5):1556-64.

- Martell MP, Atenafu EG, Minden MD, Schuh AC, Yee KW, Schimmer AD, et al. Treatment of elderly patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia using a paediatric-based protocol. British journal of haematology. 2013;163(4):458-64.

- Offidani M, Corvatta L, Centurioni R, Leoni F, Malerba L, Mele A, et al. High-dose daunorubicin as liposomal compound (Daunoxome) in elderly patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. The hematology journal : the official journal of the European Haematology Association. 2003;4(1):47-53.

- Kantarjian HM, O’Brien S, Smith T, Estey EH, Berran M, Preti A, et al. Acute lymphocytic leukaemia in the elderly: characteristics and outsome with the vincristine-adriamycin-dexamethasone (VAD) regimen. British journal of haematology. 1994;88(1):94-100.

- Asociación española de hematología y hemoterapia. Programa Español para el tratamiento de las hemopatias malignas (PETHEMA): Protocolo para el tratamiento de la Leucemia Linfoblástica Aguda con cromosoma Ph negativo en pacientes de edad avanzada (>55 años): LAL 07-OLD. 2013.

- Ribera J-M, García O, Oriol A, Gil C, Montesinos P, Bernal T, et al. Feasibility and results of subtype-oriented protocols in older adults and fit elderly patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of three prospective parallel trials from the PETHEMA group. Leukemia research. 2016;41:12-20.

- Kadan-Lottick NS, Brouwers P, Breiger D, Kaleita T, Dziura J, Northrup V, et al. Comparison of neurocognitive functioning in children previously randomly assigned to intrathecal methotrexate compared with triple intrathecal therapy for the treatment of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology. 2009;27(35):5986.

- te Loo DMW, Kamps WA, van der Does-van den Berg A, van Wering ER, de Graaf SS. Prognostic significance of blasts in the cerebrospinal fluid without pleiocytosis or a traumatic lumbar puncture in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: experience of the Dutch Childhood Oncology Group. Journal of clinical oncology. 2006;24(15):2332-6.

- Manabe A, Tsuchida M, Hanada R, Ikuta K, Toyoda Y, Okimoto Y, et al. Delay of the diagnostic lumbar puncture and intrathecal chemotherapy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who undergo routine corticosteroid testing: Tokyo Children’s Cancer Study Group study L89-12. Journal of clinical oncology. 2001;19(13):3182-7.

- Castillo L, Janic D, Jazbec APDJ, Kaiserova E, Konja J, Kovacs G, et al. ALL IC-BFM 2009.

- Hasegawa D, Manabe A, Ohara A, Kikuchi A, Koh K, Kiyokawa N, et al. The utility of performing the initial lumbar puncture on day 8 in remission induction therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: TCCSG L99‐15 study. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012;58(1):23-30.

- Liu H-C, Yeh T-C, Hou J-Y, Chen K-H, Huang T-H, Chang C-Y, et al. Triple intrathecal therapy alone with omission of cranial radiation in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(17):1825-9.

- Nachman JB, Sather HN, Sensel MG, Trigg ME, Cherlow JM, Lukens JN, et al. Augmented post-induction therapy for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia and a slow response to initial therapy. The New England journal of medicine. 1998;338(23):1663-71.

- Hastings C, Gaynon PS, Nachman JB, Sather HN, Lu X, Devidas M, et al. Increased post-induction intensification improves outcome in children and adolescents with a markedly elevated white blood cell count (>/=200 x 10(9) /l) with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia but not B cell disease: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. British journal of haematology. 2015;168(4):533-46.

- Chang JE, Medlin SC, Kahl BS, Longo WL, Williams EC, Lionberger J, et al. Augmented and standard Berlin–Frankfurt–Münster chemotherapy for treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2008;49(12):2298-307.

- Iparraguirre L, Gutierrez-Camino A, Umerez M, Martin-Guerrero I, Astigarraga I, Navajas A, et al. MiR-pharmacogenetics of methotrexate in childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2016;26(11):517-25.

- Vaishnavi K, Bansal D, Trehan A, Jain R, Attri SV. Improving the safety of high‐dose methotrexate for children with hematologic cancers in settings without access to MTX levels using extended hydration and additional leucovorin. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2018:e27241.

- Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, Harvey RC, Yang Y-L, Pei D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(11):1005-15.

- Chaar M, Kamta J, Ait-Oudhia S. Mechanisms, monitoring, and management of tyrosine kinase inhibitors–associated cardiovascular toxicities. OncoTargets and therapy. 2018;11:6227.

- Schultz K, Aledo A, Bowman W, Slayton W, Sather H, Devidas M. Improved early event free survival (EFS) with tolerable toxicity in children with philadelphia chromosome positive (Ph+) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) with intensive imatinib mesylate with dose-intensive multiagent chemotherapy: Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Study AALL0031. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5175-81.

- Biondi A, Schrappe M, De Lorenzo P, Castor A, Lucchini G, Gandemer V, et al. Imatinib after induction for treatment of children and adolescents with Philadelphia-chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (EsPhALL): a randomised, open-label, intergroup study. The lancet oncology. 2012;13(9):936-45.

- Lou Y, Ma Y, Li C, Suo S, Tong H, Qian W, et al. Efficacy and prognostic factors of imatinib plus CALLG2008 protocol in adult patients with newly diagnosed Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Frontiers of medicine. 2017;11(2):229-38.

- Wheeler KA, Richards SM, Bailey CC, Gibson B, Hann IM, Hill FGH, et al. Bone marrow transplantation versus chemotherapy in the treatment of very high–risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission: results from Medical Research Council UKALL X and XI. Blood. 2000;96(7):2412-8.

- Alberta Provincial Hematology Tumour Team. Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. In: Services AH, editor. Canada: Alberta Health Services; 2016.

- Bredeson C VN, Walker I, Kuruvilla J, Kouroukis C, Stem Cell Transplant Steering Committee,. Stem Cell Transplantation in the Treatment of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. In: Program in Evidence-Based Care CCO, editor. Canada: Cancer Care Ontario; 2016.

- Ciurea SO, Bittencourt MCB, Milton DR, Cao K, Kongtim P, Rondon G, et al. Is a matched unrelated donor search needed for all allogeneic transplant candidates? Blood Adv. 2018;2(17):2254-61.

- Aversa F, Berneman ZN, Locatelli F, Martelli MF, Reisner Y, Tabilio A, et al. Fourth international workshop on haploidentical transplants, Naples, Italy, July 8–10, 2004. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2004;33(3):159-75.

- Bashey A, Zhang X, Jackson K, Brown S, Ridgeway M, Solh M, et al. Comparison of Outcomes of Hematopoietic Cell Transplants from T-Replete Haploidentical Donors Using Post-Transplantation Cyclophosphamide with 10 of 10 HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 Allele-Matched Unrelated Donors and HLA-Identical Sibling Donors: A Multivariable Analysis Including Disease Risk Index. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(1):125-33.

- Yang B, Yu R, Cai L, Bin G, Chen H, Zhang H, et al. Haploidentical versus matched donor stem cell transplantation for patients with hematological malignancies: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Bone marrow transplantation. 2019;54(1):99-122.

- Gao L, Zhang C, Gao L, Liu Y, Su Y, Wang S, et al. Favorable outcome of haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a multicenter study in Southwest China. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2015;8:90.

- Han LJ, Wang Y, Fan ZP, Huang F, Zhou J, Fu YW, et al. Haploidentical transplantation compared with matched sibling and unrelated donor transplantation for adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in first complete remission. British journal of haematology. 2017;179(1):120-30.

- Slade M, DiPersio JF, Westervelt P, Vij R, Schroeder MA, Romee R. Haploidentical Hematopoietic Cell Transplant with Post-Transplant Cyclophosphamide and Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Grafts in Older Adults with Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2017;23(10):1736-43.

- Piemontese S, Ciceri F, Labopin M, Arcese W, Kyrcz-Krzemien S, Santarone S, et al. A comparison between allogeneic stem cell transplantation from unmanipulated haploidentical and unrelated donors in acute leukemia. Journal of hematology & oncology. 2017;10(1):24.

- Solomon SR, Sizemore CA, Zhang X, Brown S, Holland HK, Morris LE, et al. Impact of Donor Type on Outcome after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Acute Leukemia. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(10):1816-22.

- Rashidi A, DiPersio JF, Westervelt P, Vij R, Schroeder MA, Cashen AF, et al. Comparison of Outcomes after Peripheral Blood Haploidentical versus Matched Unrelated Donor Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Retrospective Single-Center Review. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(9):1696-701.

- Ciurea SO, Zhang MJ, Bacigalupo AA, Bashey A, Appelbaum FR, Aljitawi OS, et al. Haploidentical transplant with posttransplant cyclophosphamide vs matched unrelated donor transplant for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2015;126(8):1033-40.

- Abdul Wahid SF, Ismail NA, Mohd-Idris MR, Jamaluddin FW, Tumian N, Sze-Wei EY, et al. Comparison of reduced-intensity and myeloablative conditioning regimens for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a meta-analysis. Stem cells and development. 2014;23(21):2535-52.

- Champlin RE, Passweg JR, Zhang M-J, Rowlings PA, Pelz CJ, Atkinson KA, et al. T-cell depletion of bone marrow transplants for leukemia from donors other than HLA-identical siblings: advantage of T-cell antibodies with narrow specificities. Blood. 2000;95(12):3996-4003.

Si tienes comentarios sobre el contenido de las guías de práctica clínica, puedes comunicarte con IETSI-EsSalud enviando un correo: gpcdireccion.ietsi@essalud.gob.pe

SUGERENCIAS

Si has encontrado un error en esta página web o tienes alguna sugerencia para su mejora, puedes comunicarte con EviSalud enviando un correo a evisalud@gmail.com