DESCARGAR

VERSIÓN EXTENSA

DESCARGAR

ANEXOS

DESCARGAR

VERSIÓN CORTA

DESCARGAR RECOMENDACIONES Y FLUJOGRAMAS

vacio

vacio

Ámbito

- •El ámbito asistencial incluye los servicios de medicina interna, cardiología, radiología con formación en imágenes cardiovasculares, cirugía cardiovascular, en lo que corresponda a cada nivel de atención en EsSalud..

Población y alcance

•Pacientes de 18 años a más con diagnóstico de síndrome coronario crónico asegurados a EsSalud.

Autores

Grupo elaborador de la versión actualizada de la guía (2024)

Expertos clínicos:

- Violeta Illatopa Cerna

Médico cardióloga, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular “Carlos Alberto Peschiera Carrillo” (INCOR), EsSalud, Lima, Perú - David Germán Gálvez Caballero

Médico cardiólogo, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular “Carlos Alberto Peschiera Carrillo” (INCOR), EsSalud, Lima, Perú - Cecilia Aurora Cuevas De La Cruz

Médico cardióloga intervencionista, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular “Carlos Alberto Peschiera Carrillo” (INCOR), EsSalud, Lima, Perú - Gladys Martha Espinoza Rivas

Médico cardióloga, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular “Carlos Alberto Peschiera Carrillo” (INCOR), EsSalud, Lima, Perú - Aurelio Mendoza Paulini

Médico cardiólogo y especialista en Medicina Nuclear, Instituto Nacional Cardiovascular “Carlos Alberto Peschiera Carrillo” (INCOR), EsSalud, Lima, Perú

Metodólogos:

- Ana Lida Brañez Condorena

Metodóloga, IETSI, EsSalud, Lima, Perú - Mario Enrique Díaz Barrera

Metodólogo, IETSI, EsSalud, Lima, Perú

Coordinadoras del grupo elaborador:

- Joan Caballero Luna

IETSI, EsSalud, Lima, Perú - Fabiola Mercedes Huaroto Ramírez

IETSI, EsSalud, Lima, Perú

Metodología

Resumen de la metodología:

- Conformación del GEG: La Dirección de Guías de Práctica Clínica, Farmacovigilancia y Tecnovigilancia, del Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación (IETSI) del Seguro Social del Perú (EsSalud), conformó un grupo elaborador de la guía (GEG), que incluyó médicos especialistas y metodólogos.

- Planteamiento de preguntas clínicas: En concordancia con los objetivos y alcances de esta GPC, se formularon las preguntas clínicas.

- Búsqueda de la evidencia para cada pregunta: Para cada pregunta clínica, se realizaron búsquedas de revisiones sistemáticas (publicadas como artículos científicos o guías de práctica clínica). De no encontrar revisiones de calidad, se buscaron estudios primarios, cuyo riesgo de sesgo fue evaluado usando herramientas estandarizadas.

- Evaluación de la certeza de la evidencia: Para graduar la certeza de la evidencia, se siguió la metodología Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE), y se usaron tablas de Summary of Findings (SoF).

- Formulación de las recomendaciones: El GEG revisó la evidencia recolectada para cada una de las preguntas clínicas en reuniones periódicas, en las que formuló las recomendaciones usando la metodología GRADE, otorgándole una fuerza a cada una. Para ello, se tuvo en consideración los beneficios y daños de las opciones, valores y preferencias de los pacientes, aceptabilidad, factibilidad, equidad y uso de recursos. Estos criterios fueron presentados y discutidos, tomando una decisión por consenso o mayoría simple. Asimismo, el GEG emitió puntos de buenas prácticas clínicas (BPC) sin una evaluación formal de la evidencia, y mayormente en base a su experiencia clínica.

- Revisión externa: La presente GPC fue revisada en reuniones con profesionales representantes de otras instituciones, tomadores de decisiones, y expertos externos.

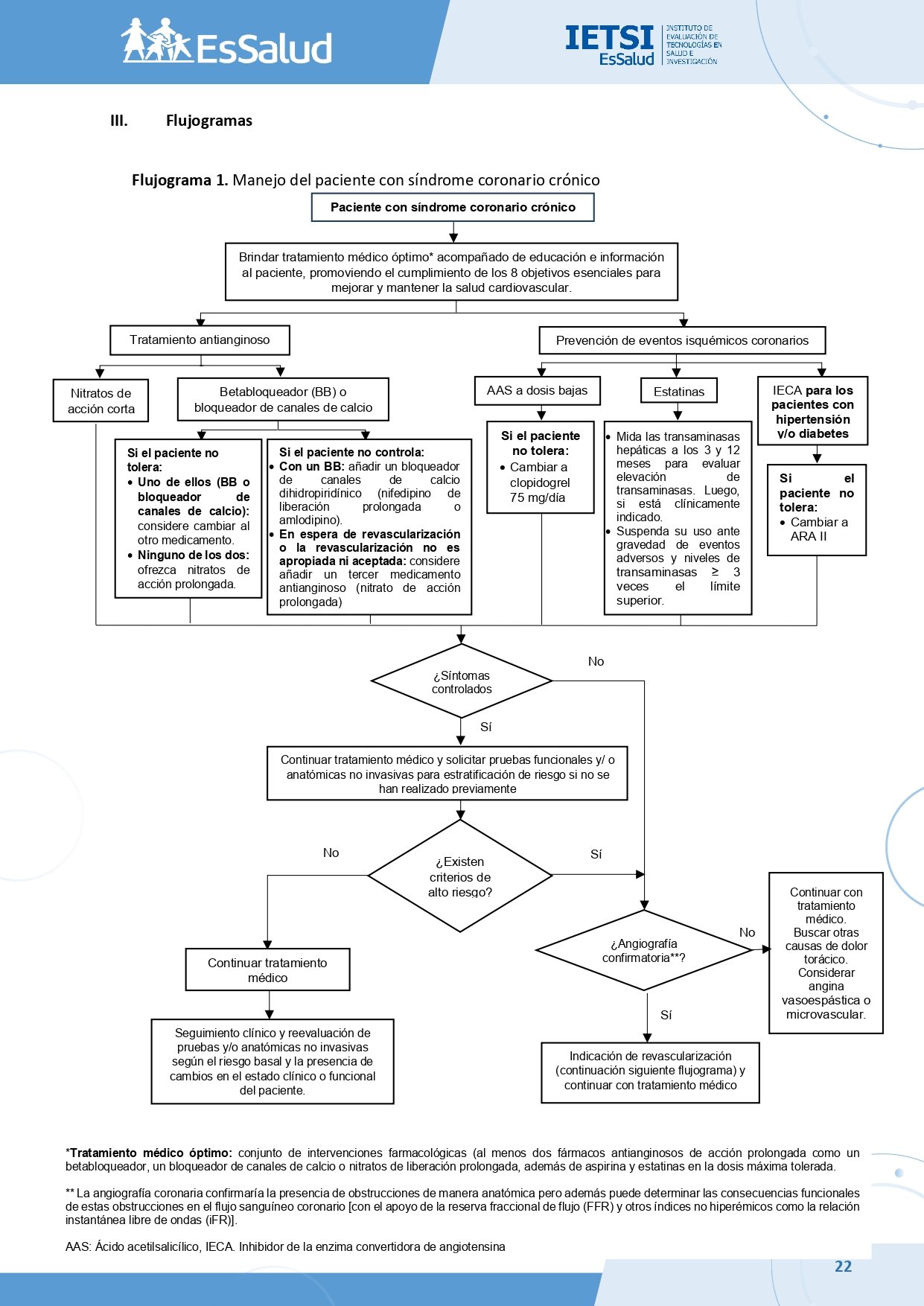

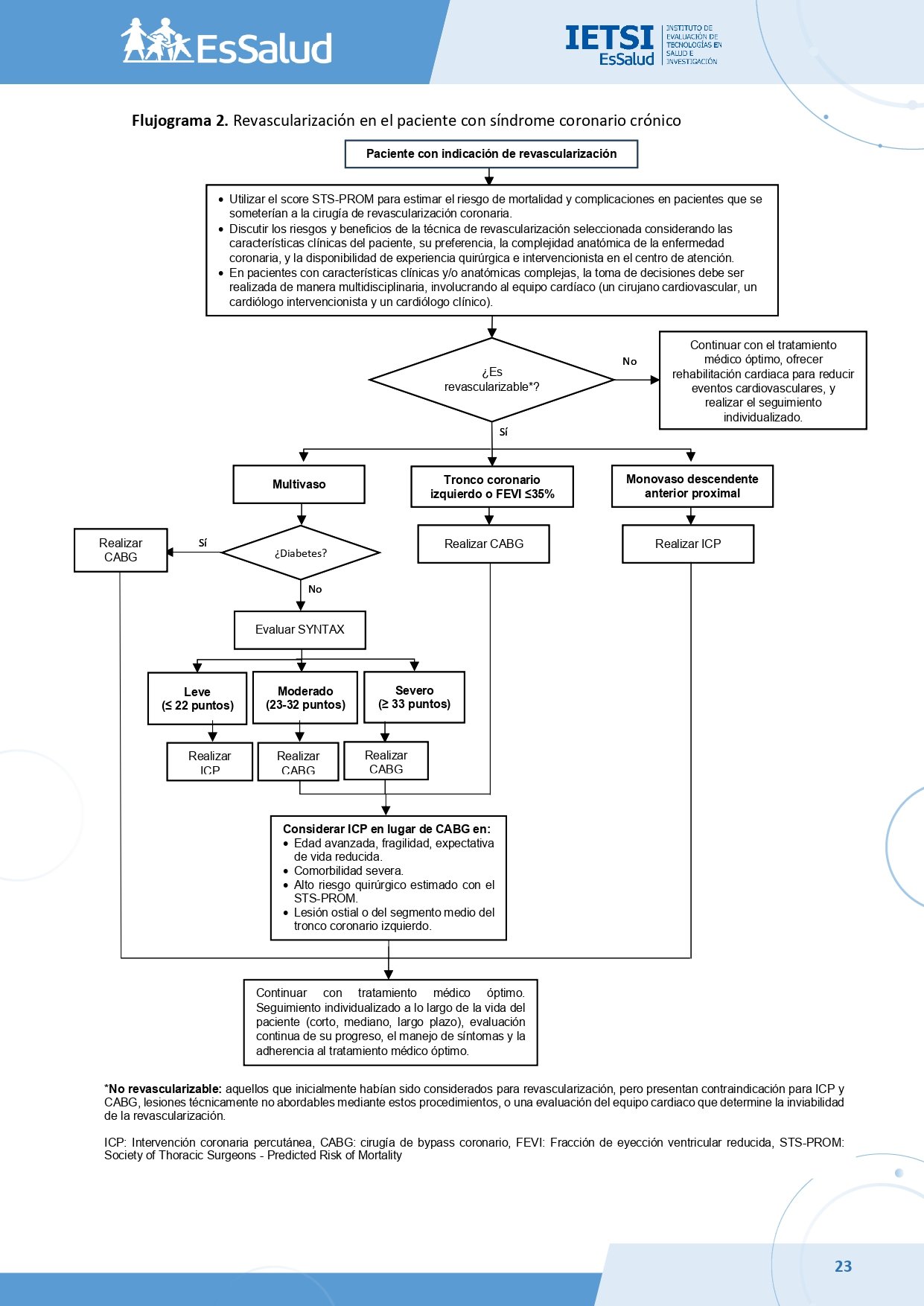

Flujogramas que resumen el contenido de la GPC

vacio

vacio

1. Participación en decisiones de tratamiento

BPC 1:

Aconseje al paciente sobre la necesidad de cambios en su estilo de vida (ejercicio, dejar de fumar, control del peso y consejería nutricional) y apoyo psicológico. Ofrezca intervención para el control de factores de riesgo, de ser necesario.

BPC 2:

Eduque al paciente acerca del síndrome coronario crónico, sus síntomas y factores desencadenantes (ejercicio, estrés emocional, exposición al frío, alimentos de difícil digestión), así como sobre su evolución a corto y largo plazo, manejo y seguimiento. Involucre a la familia y/o cuidador del paciente en la discusión.

BPC 3:

Aborde las necesidades del paciente en relación con el síndrome coronario crónico, que pueden incluir:

- Estrategias para regular sus actividades y establecer metas.

- Preocupaciones sobre el estrés, ansiedad o depresión.

- Orientación sobre ejercicio físico y actividad sexual.

- Consejería en alimentación saludable.

BPC 4:

Dialogue sobre las ideas, preocupaciones y expectativas del paciente, su familia y/o cuidador, motivando a expresar sus dudas sobre su condición, pronóstico y tratamiento. Aclare cualquier malinterpretación sobre la enfermedad y sus implicaciones para la vida diaria, el riesgo de infarto y la expectativa de vida.

BPC 5:

Explique al paciente que el objetivo del tratamiento antianginoso es reducir los episodios de angina, mientras que el objetivo del tratamiento de prevención secundaria es prevenir eventos como muerte, infarto o enfermedad cerebrovascular.

BPC 6:

Los pacientes son diferentes en cuanto al tipo y cantidad de información que necesitan y desean. Por eso, la provisión de información debe individualizarse y puede incluir, pero no limitarse a:

- Identificación de síntomas de alarma.

- En qué consisten y cómo usar los medicamentos.

- Cómo beneficiarán los medicamentos a su condición.

- Posibles efectos adversos y qué hacer si creen que están experimentando alguno.

- Qué hacer si olvidan una dosis.

- Si será necesario continuar o ajustar el tratamiento después de la primera prescripción.

- Cómo solicitar más medicamentos.

BPC 7:

Explique al paciente que debe acudir a emergencia si tiene un empeoramiento súbito en la frecuencia o severidad de su angina.

2. Estratificación de riesgo

BPC 1:

En pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico, realizar la estratificación del riesgo en aquellos que:

- Han completado un tratamiento médico inicial óptimo con control de síntomas, pero presentan factores de riesgo adicionales o antecedentes de complicaciones.

- Presentaban previamente una condición estable, pero han desarrollado síntomas nuevos o experimentan un empeoramiento de los síntomas que no corresponden a angina inestable.

BPC 2:

En pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico, determinar la estratificación del riesgo: riesgo bajo (<1%), riesgo intermedio (1-3%) y alto riesgo (>3%) de muerte o infarto de miocardio, considerando la información individualizada de cada paciente y el resultado validado de alguna de las siguientes pruebas funcionales y/o anatómicas no invasivas según la experiencia y la disponibilidad local:

- Prueba de esfuerzo con electrocardiograma (ECG).

- Ecocardiografía por estrés.

- Perfusión miocárdica mediante tomografía computarizada de emisión de fotón único (SPECT).

- Resonancia magnética cardiaca de estrés.

- Angiotomografía coronaria.

BPC 3:

Considere que los pacientes a ser sometidos a las pruebas funcionales o anatómicas no invasivas para la estratificación del riesgo deben continuar con la terapia farmacológica para síndrome coronario crónico durante la realización de las pruebas.

BPC 4:

Considere determinar la estratificación del alto riesgo de muerte o infarto de miocardio por pruebas funcionales o anatómicas no invasivas según los criterios de la Tabla N° 1.

BPC 5:

La prueba de esfuerzo no debe utilizarse para descartar enfermedad coronaria debido a la alta tasa de falsos negativos y falsos positivos. Sin embargo, puede ser útil en pacientes con resultados positivos de alto riesgo (Score de Duke ≤ -11) para identificar aquellos con mayor riesgo de muerte o infarto no fatal. Se debe limitar su aplicación a situaciones en las que no estén disponibles otras pruebas de estratificación del riesgo.

BPC 6:

Considere los siguientes escenarios, según las características clínicas específicas de cada paciente, para una valoración de riesgo y manejo individualizado que incluya un seguimiento estrecho (cada 1-3 meses) por el cardiólogo, brindar tratamiento médico óptimo y realizar una evaluación continua de los síntomas:

- Para pacientes con Score de Duke > -11 con una historia clínica sugerente de síndrome coronario crónico.

- Para pacientes con un porcentaje de isquemia del 10-20% según la perfusión miocárdica mediante SPECT.

BPC 7:

En pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico, considere realizar el seguimiento por lo menos cada 3 meses por el cardiólogo, incluyendo la estratificación del riesgo de muerte o infarto de miocardio mediante la reevaluación con pruebas funcionales o anatómicas no invasivas, según el riesgo basal y la presencia de cambios en el estado clínico o funcional del paciente.

3. Tratamiento médico óptimo o revascularización

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, sugerimos brindar tratamiento médico óptimo, y decidir agregar o no la revascularización para alivio de síntomas según el estado funcional del paciente, comorbilidades y experiencia del equipo quirúrgico o intervencionista.

Consideraciones:

- El tratamiento médico óptimo consiste en el conjunto de intervenciones farmacológicas y no farmacológicas dirigidas a controlar los síntomas, prevenir eventos isquémicos coronarios y mejorar la calidad de vida de los pacientes.

- Incluye al menos dos fármacos antianginosos de acción prolongada (como un betabloqueador, bloqueador de canales del calcio o nitratos de liberación prolongada), además de un antiagregante plaquetario y estatinas en la dosis máxima tolerada. Las opciones disponibles en EsSalud se detallan en la Tabla N° 2.

(Recomendación condicional a favor, certeza baja de la evidencia)

BPC 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, considerar la revascularización en los pacientes cuyos síntomas no se controlan satisfactoriamente con el tratamiento médico óptimo.

BPC 3:

Promueva el cumplimiento de los 8 objetivos esenciales para mejorar y mantener la salud cardiovascular.

- Alimentación saludable: Adoptar una dieta balanceada rica en frutas, verduras, granos integrales y baja en grasas saturadas y azúcares.

- Actividad física: Realizar al menos 150 minutos de actividad aeróbica moderada o 75 minutos de actividad intensa por semana.

- No fumar/nicotina: Evitar el consumo de tabaco y productos relacionados, incluidos cigarrillos electrónicos.

- Peso saludable: Obtener y mantener un índice de masa corporal (IMC) entre 18.5 y 25 kg/m².

- Presión arterial saludable: Mantener la presión arterial por debajo de 120/80 mmHg. En hipertensos, el objetivo es lograr una presión sistólica de <130 mmHg*

- Colesterol saludable: Controlar los niveles de colesterol no-HDL a menos de 100 mg/dL.

- Glucosa saludable: Mantener la glucosa en sangre en ayunas por debajo de 100 mg/dL. En diabéticos, el objetivo de HbA1c es ≤ 7.0% (53 mmol/mol)*

- Sueño saludable: Dormir entre 7 y 9 horas por noche.

BPC 4:

Evalúe la respuesta del tratamiento médico óptimo dentro de un periodo mínimo de 6 semanas a 3 meses, dependiendo de la situación clínica del paciente. En ese momento se realizará una revisión completa del plan terapéutico para ajustar el tratamiento según los resultados obtenidos y las necesidades individuales.

BPC 5:

Discuta cómo los efectos secundarios del tratamiento farmacológico pueden afectar las actividades diarias del paciente y explique la importancia de la adherencia al mismo.

BPC 6:

No excluya del tratamiento a un paciente con síndrome coronario crónico basado únicamente en su edad.

BPC 7:

El enfoque de manejo del síndrome coronario crónico no debe variar entre hombres y mujeres ni entre diferentes grupos étnicos.

Recomendación 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico de alto riesgo, sugerimos brindar revascularización acompañada de tratamiento médico óptimo para disminuir la persistencia de angina.

Consideraciones:

- Paciente clasificado como de alto riesgo según los criterios descritos en la Tabla N° 1.

(Recomendación condicional a favor, certeza muy baja de la evidencia)

Recomendación 3:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico con fracción de eyección de ventrículo izquierdo reducida (≤35%), recomendamos brindar revascularización coronaria acompañada de tratamiento médico óptimo conforme a los lineamientos establecidos para esta patología, con el fin de reducir la mortalidad y la necesidad de revascularización repetida.

(Recomendación fuerte a favor, certeza moderada de la evidencia)

BPC 8:

Al identificar angiografía confirmatoria, continuar con la indicación de revascularización. Si no se identifica angiografía confirmatoria, buscar otras causas de dolor torácico y considerar angina vasoespástica o microvascular.

Consideraciones:

- La angiografía coronaria confirma la presencia de obstrucciones de forma anatómica y puede evaluar sus consecuencias funcionales (por ejemplo, mediante reserva fraccional de flujo [FFR] o índices como iFR).

BPC 9:

En pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico que presenten alguno de los siguientes hallazgos en pruebas funcionales para estratificación de riesgo intermedio:

- Score de Duke entre -11 y -4.

- Porcentaje de isquemia del 10-20% evaluado mediante perfusión miocárdica con SPECT.

- Afectación de 2 de los 16 segmentos evaluados por ecocardiografía de estrés con dobutamina.

- Defecto de perfusión transmural persistente en al menos 1 de los 16 segmentos evaluados por resonancia magnética cardiaca.

Individualice la decisión de realizar revascularización junto con tratamiento médico óptimo solo si se prevé beneficio en la reducción de episodios anginosos y/o en la disminución de revascularizaciones no planificadas.

4. Nitratos de acción corta en angina

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, sugerimos brindar nitratos de acción corta para el alivio inmediato de la angina y antes de realizar ejercicio físico.

(Recomendación condicional a favor, certeza baja de la evidencia)

BPC 2:

Para el uso de nitratos por vía oral, considere la administración en dosis excéntricas (es decir, con un periodo libre del fármaco de 10 horas) con el objetivo de reducir el riesgo de taquifilaxia o fenómeno de tolerancia.

BPC 3:

Aconseje al paciente:

- Reposo físico ante un episodio de dolor anginoso. Si el dolor no calma con el reposo, administrar nitrato.

- Sentarse antes de usar un nitrato de acción corta vía sublingual.

- Repetir la dosis luego de 5 minutos si el dolor no cede.

- Acudir a emergencia si el dolor persiste luego de 5 minutos de tomar la segunda dosis.

- Acudir a cita con cardiología, si nota que los episodios de dolor precordial se presentan a menor esfuerzo o en reposo.

- Cómo administrar el nitrato.

- Los efectos secundarios como el rubor (flushing), cefalea y mareos.

- Sentarse o encontrar algo a qué aferrarse cuando sienta mareos.

5. Antianginosos como manejo inicial

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, sugerimos iniciar el tratamiento con un betabloqueador o un bloqueador de canales de calcio, teniendo en cuenta las comorbilidades, contraindicaciones y preferencias del paciente.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

BPC 2:

Luego de haber iniciado o cambiado el tratamiento farmacológico, evalúe la respuesta al tratamiento, incluyendo cualquier efecto secundario, a las 2-4 semanas.

BPC 3:

Titule la dosis de acuerdo con los síntomas del paciente hasta la máxima dosis tolerable.

BPC 4:

Si el paciente no tolera el betabloqueador o el bloqueador de canales de calcio como tratamiento inicial, considere cambiar al otro medicamento.

BPC 5:

En paciente que no toleren ni betabloqueadores ni bloqueadores de canales de calcio, ofrezca nitratos de acción prolongada.

Recomendación 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico cuyos síntomas anginosos no se controlen con un betabloqueador, sugerimos añadir un bloqueador de canales de calcio en lugar de un nitrato de acción prolongada.

Consideraciones:

- Al combinar un betabloqueador con un bloqueador de canales de calcio, use un dihidropiridínico (nifedipino de liberación prolongada o amlodipino).

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

BPC 7:

No ofrezca de forma rutinaria medicamentos antianginosos diferentes a betabloqueadores o bloqueadores de canales de calcio como tratamiento de primera línea para síndrome coronario crónico.

BPC 8:

No añada un tercer medicamento antianginoso en pacientes cuya angina esté controlada con dos medicamentos antianginosos.

BPC 9:

En pacientes que esperan una revascularización, o en quienes la revascularización no es apropiada o no es aceptada por el paciente, considere añadir un tercer medicamento antianginoso (nitrato de acción prolongada).

BPC 10:

No administre un bloqueador de calcio dihidropiridínico de acción corta (nifedipino 10 mg) en pacientes con enfermedad arterial coronaria y episodios anginosos.

6. Antiagregantes plaquetarios

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

✩ En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico sugerimos usar dosis bajas de ácido acetilsalicílico (75 a 100 mg/día), teniendo en cuenta el riesgo de sangrado y comorbilidades del paciente.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

BPC 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico que no toleren el ácido acetilsalicílico, prescriba clopidogrel 75 mg por día.

7. IECA o ARA II en HTA y/o DM

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico con hipertensión y/o diabetes, sugerimos brindar un IECA.

Consideraciones:

- El objetivo del tratamiento en pacientes con hipertensión es lograr valores de presión arterial sistólica <130 mmHg, siempre que el tratamiento antihipertensivo sea bien tolerado.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

BPC 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico con hipertensión y/o diabetes y que no toleran los IECA, brinde un ARA-II considerando las características del paciente.

8. Estatinas

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, recomendamos brindar estatinas.

Consideraciones:

- Los objetivos del tratamiento son LDL colesterol (c-LDL) en ayunas < 1,4 mmol/l (< 55 mg/dl) o una reducción del c-LDL en ayunas en al menos un 50% desde el valor inicial, a los 3 meses de tratamiento.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Fuerte, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

BPC 2:

Decida el uso de estatinas tras una discusión informada entre el médico y el paciente sobre los riesgos y beneficios del tratamiento, teniendo en cuenta la polifarmacia, cambios en el estilo de vida y comorbilidades.

BPC 3:

Titule la dosis de estatinas, dependiendo del logro de los objetivos del tratamiento y la presencia de eventos adversos del paciente, hasta la máxima dosis tolerable.

BPC 4:

Indique a las personas en tratamiento con estatinas que acudan al médico si presentan algún síntoma o signo muscular (dolor, sensibilidad o debilidad muscular; o rabdomiólisis) o reportan la presencia de estos síntomas en la evaluación con su médico tratante. Evaluar si estos efectos adversos son debidos a las estatinas, y considerar suspender su uso según la dosis administrada y la gravedad de los eventos adversos.

BPC 5:

Mida las transaminasas hepáticas a los 3 meses y a los 12 meses del inicio del tratamiento con estatinas para evaluar si el paciente presenta elevación de transaminasas. Posterior a los 12 meses, reevaluar las transaminasas si está clínicamente indicado. Si se superan niveles de transaminasas ≥ 3 veces el límite superior, suspender el uso de estatinas.

9. Omega 3

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, sugerimos no brindar las cápsulas de aceite de pescado (suplementación de omega 3).

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

10. ICP o CABG

Descargar PDF con el desarrollo de la pregunta.

BPC 1:

Utilice el score STS-PROM (Society of Thoracic Surgeons – Predicted Risk of Mortality) para estimar el riesgo de mortalidad y complicaciones en pacientes que irían a cirugía de bypass aorto coronario.

Score de la Sociedad de Cirujanos Torácicos (STS-PROM): Información utilizada para el cálculo del riesgo quirúrgico:

- Cirugía planificada (tipo, incidencia, prioridad quirúrgica)

- Datos demográficos (sexo, edad, talla, peso, IMC, raza)

- Resultados de laboratorio (creatinina, hematocrito, recuento de leucocitos, recuento de plaquetas)

- Factores de riesgo/comorbilidades

- Estado cardiaco

- Enfermedad arterial coronaria, enfermedad valvular y/o arritmias

- Intervención cardiaca previa

El cálculo se realiza mediante un programa informático a través del siguiente enlace: https://www.sts.org/resources/acsd-operative-risk-calculator

BPC 2:

Utilice el score SYNTAX para estratificar la complejidad angiográfica de las estenosis coronarias significativas en pacientes con enfermedad multivaso, con o sin compromiso del tronco coronario izquierdo.

Score SYNTAX: Información utilizada para el cálculo:

- Dominancia (derecha, izquierda)

- Número de lesiones

- Segmentos involucrados por lesión

- Presencia de oclusión total

- Presencia de trifurcación

- Presencia de bifurcación

- Lesión aorto-ostial

- Tortuosidad severa

- Longitud >20 mm

- Calcificación severa

- Trombosis

- Enfermedad difusa/vasos pequeños

La puntuación se obtiene sumando los puntos de cada criterio evaluado: 0-22 (Leve), 23-32 (Moderado), >33 (Severo).

Recomendación 1:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad monovaso de la arteria descendente anterior proximal, sugerimos brindar ICP en lugar de CABG.(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Muy baja)

Recomendación 2:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad de tronco coronario izquierdo, sugerimos brindar CABG en lugar de ICP, para reducir eventos de revascularización repetida e infarto de miocardio.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Muy baja)

BPC 3:

Considerar la ICP en lugar de la CABG como opción en pacientes con lesión localizada en el ostium o en el segmento medio del tronco coronario izquierdo, cuando las características anatómicas permitan un abordaje técnicamente favorable.

Recomendación 3:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico, diabetes y enfermedad multivaso, sugerimos brindar CABG en lugar de ICP.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Muy baja)

Recomendación 4:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad multivaso con SYNTAX leve (≤ 22 puntos), sugerimos brindar ICP en lugar de CABG.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

Recomendación 5:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad multivaso con SYNTAX moderado (23-32 puntos), sugerimos brindar CABG en lugar de ICP para reducir eventos de revascularización repetida e infarto de miocardio.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

Recomendación 6:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad multivaso con SYNTAX severo (≥ 33 puntos), sugerimos brindar CABG en lugar de ICP.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Baja)

Recomendación 7:

En pacientes adultos con síndrome coronario crónico y fracción de eyección ventricular izquierda reducida (≤35%), sugerimos preferir CABG sobre ICP, tras una evaluación minuciosa, idealmente realizada por un equipo cardíaco multidisciplinario que considere las características clínicas y anatómicas del paciente, así como sus preferencias.

(Fuerza de la recomendación: Condicional, Certeza de la evidencia: Muy baja)

BPC 4:

En pacientes con enfermedad multivaso y/o enfermedad del tronco coronario izquierdo que requieren CABG, la revascularización debe incluir injertos arteriales, preferentemente utilizando la arteria mamaria o la arteria radial.

BPC 5:

En pacientes con características clínicas y/o anatómicas complejas, la toma de decisiones debe ser realizada de manera multidisciplinaria, involucrando al equipo cardiaco (cirujano cardiovascular, cardiólogo intervencionista y cardiólogo clínico).

BPC 6:

En pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico y enfermedad de tronco coronario izquierdo y/o multivaso, considere los siguientes escenarios para elegir ICP en lugar de CABG previa evaluación del equipo cardiaco:

- Edad avanzada, fragilidad, expectativa de vida reducida.

- Comorbilidad severa.

- Alto riesgo quirúrgico estimado con el STS-PROM.

BPC 7:

Discutir los riesgos y beneficios de la técnica de revascularización seleccionada considerando las características clínicas del paciente, su preferencia, la complejidad anatómica de la enfermedad coronaria y la disponibilidad de experiencia quirúrgica e intervencionista en el centro de atención.

BPC 8:

Para los pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico que se someten a revascularización, realice un seguimiento individualizado a lo largo de su vida (corto, mediano, largo plazo). Asegúrese de evaluar continuamente su progreso, manejo de síntomas y adherencia al tratamiento médico óptimo, realizando ajustes en la terapia según sea necesario para prevenir y monitorizar posibles eventos de enfermedad cerebrovascular, infarto de miocardio y la necesidad de revascularización repetida.

BPC 9:

En los pacientes con síndrome coronario crónico no revascularizables (aquellos inicialmente considerados para revascularización, pero con contraindicación para ICP y CABG, lesiones técnicamente no abordables o evaluados como inviables por el equipo cardiaco), continuar con el tratamiento médico óptimo, ofrecer rehabilitación cardiaca para reducir eventos cardiovasculares y realizar seguimiento individualizado.

Referencias bibliográficas

1. Zellweger MJ, Dubois EA, Lai S, Shaw LJ, Amanullah AM, Lewin HC, et al. Risk stratification in patients with remote prior myocardial infarction using rest-stress myocardial perfusion SPECT: prognostic value and impact on referral to early catheterization. Journal of nuclear cardiology : official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2002;9(1):23-32.

2. Hachamovitch R, Berman DS, Kiat H, Cohen I, Cabico JA, Friedman J, et al. Exercise myocardial perfusion SPECT in patients without known coronary artery disease: incremental prognostic value and use in risk stratification. Circulation. 1996;93(5):905-14.

3. Senior R, Monaghan M, Becher H, Mayet J, Nihoyannopoulos P. Stress echocardiography for the diagnosis and risk stratification of patients with suspected or known coronary artery disease: a critical appraisal. Supported by the British Society of Echocardiography. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2005;91(4):427-36.

4. Mazzanti M, Germano G, Kiat H, Kavanagh PB, Alexanderson E, Friedman JD, et al. Identification of severe and extensive coronary artery disease by automatic measurement of transient ischemic dilation of the left ventricle in dual-isotope myocardial perfusion SPECT. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1996;27(7):1612-20.

5. Abidov A, Bax JJ, Hayes SW, Hachamovitch R, Cohen I, Gerlach J, et al. Transient ischemic dilation ratio of the left ventricle is a significant predictor of future cardiac events in patients with otherwise normal myocardial perfusion SPECT. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;42(10):1818-25.

6. Williams KA, Schneider CM. Increased stress right ventricular activity on dual isotope perfusion SPECT: a sign of multivessel and/or left main coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;34(2):420-7.

7. Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el Manejo de pacientes con Angina Estable: Guía en Versión Extensa. Lima: EsSalud; 2018.

8. Instituto de Evaluación de Tecnologías en Salud e Investigación. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el manejo de pacientes con angina estable – Actualización: Guía en Versión Extensa. Lima: EsSalud; 2023.

9. Ueng KC, Chiang CE, Chao TH, Wu YW, Lee WL, Li YH, et al. 2023 Guidelines of the Taiwan Society of Cardiology on the Diagnosis and Management of Chronic Coronary Syndrome. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2023;39(1):4-96.

10. Virani SS, Newby LK, Arnold SV, Bittner V, Brewer LC, Demeter SH, et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Chronic Coronary Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2023;148(9):e9-e119.

11. Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, Rossello X, Adamo M, Ainslie J, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. European heart journal. 2024;45(36):3415-537.

12. Zhang S, Chen S, Yang K, Li Y, Yun Y, Zhang X, et al. Minimally Invasive Direct Coronary Artery Bypass Versus Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Isolated Left Anterior Descending Artery Stenosis: An Updated Meta-Analysis. The heart surgery forum. 2023;26(1):E114-e25.

13. Hennessy C, Henry J, Parameswaran G, Brameier D, Kharbanda R, Myerson S. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention vs. Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in Left Main Coronary Artery Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2023;15(11):e48297.

14. Gallo M, Blitzer D, Laforgia PL, Doulamis IP, Perrin N, Bortolussi G, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass graft for left main coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2022;163(1):94-105.e15.

15. D’Ascenzo F, De Filippo O, Elia E, Doronzo MP, Omedè P, Montefusco A, et al. Percutaneous vs. surgical revascularization for patients with unprotected left main stenosis: a meta-analysis of 5-year follow-up randomized controlled trials. European heart journal Quality of care & clinical outcomes. 2021;7(5):476-85.

16. Akintoye E, Salih M, Olagoke O, Oseni A, Sistla P, Alqasrawi M, et al. Intermediate and Late Outcomes With PCI vs CABG for Left Main Disease – Landmark Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Cardiovascular revascularization medicine : including molecular interventions. 2021;23:114-8.

17. Cui KY, Lyu SZ, Song XT, Yuan F, Xu F, Zhang M, et al. Long term outcomes of drug-eluting stent versus coronary artery bypass grafting for left main coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. Journal of geriatric cardiology : JGC. 2018;15(2):162-72.

18. Sá M, Soares AF, Miranda RGA, Araújo ML, Menezes AM, Silva FPV, et al. CABG Surgery Remains the best Option for Patients with Left Main Coronary Disease in Comparison with PCI-DES: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Brazilian journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2017;32(5):408-16.

19. Qian C, Feng H, Cao J, Wei B, Wang Y. Meta-Analysis of Randomized Control Trials Comparing Drug-Eluting Stents Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Significant Left Main Coronary Narrowing. The American journal of cardiology. 2017;119(9):1338-43.

20. Gao L, Liu Y, Sun Z, Wang Y, Cao F, Chen Y. Percutaneous coronary intervention using drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass graft surgery in left main coronary artery disease an updated meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66449-57.

21. Xie Q, Huang J, Zhu K, Chen Q. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Cumulative meta-analysis. Clinical cardiology. 2021;44(7):899-906.

22. Zhai C, Cong H, Hou K, Hu Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y. Clinical outcome comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention and bypass surgery in diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and observational studies. Diabetology & metabolic syndrome. 2019;11:110.

23. Thuijs D, Kappetein AP, Serruys PW, Mohr FW, Morice MC, Mack MJ, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease: 10-year follow-up of the multicentre randomised controlled SYNTAX trial. Lancet (London, England). 2019;394(10206):1325-34.

24. Thuijs D, Milojevic M, Stone GW, Puskas JD, Serruys PW, Sabik JF, 3rd, et al. Impact of left ventricular ejection fraction on clinical outcomes after left main coronary artery revascularization: results from the randomized EXCEL trial. European journal of heart failure. 2020;22(5):871-9.

25. Bhandari B, Quintanilla Rodriguez BS, Masood W. Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

26. Gillen C, Goyal A. Stable Angina. [Updated 2022 Dec 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

27. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2010;182(18):E839-E42.

28. Ministerio de Salud. Documento técnico: Metodología para la de documento técnico elaboración guías de practica clínica. Lima, Perú: MINSA; 2015.

29. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Stable angina. NICE 2011-2016 Nov:CG172 PDF.

30. Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;358:j4008.

31. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2011;343:d5928.

32. Wells GA, Wells G, Shea B, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al., editors. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses2014.

33. Andrews JC, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Pottie K, Meerpohl JJ, Coello PA, et al. GRADE guidelines: 15. Going from evidence to recommendation—determinants of a recommendation’s direction and strength. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2013;66(7):726-35.

34. Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD, Alderson P, Dahm P, Falck-Ytter Y, et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2013;66(7):719-25.

35. Valgimigli M, Biscaglia S. Stable angina pectoris. Current atherosclerosis reports. 2014;16(7):422.

36. McGillion MH, Watt-Watson JH, Kim J, Graham A. Learning by heart: a focused group study to determine the self-management learning needs of chronic stable angina patients. Canadian journal of cardiovascular nursing = Journal canadien en soins infirmiers cardio-vasculaires. 2004;14(2):12-22.

37. Pier C, Shandley KA, Fisher JL, Burstein F, Nelson MR, Piterman L. Identifying the health and mental health information needs of people with coronary heart disease, with and without depression. The Medical journal of Australia. 2008;188(S12):S142-4.

38. Weetch RM. Patient satisfaction with information received after a diagnosis of angina. Professional nurse (London, England). 2003;19(3):150-3.

39. Karlik BA, Yarcheski A, Braun J, Wu M. Learning needs of patients with angina: an extension study. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing. 1990;4(2):70-82.

40. Shi W, Ghisi GLM, Zhang L, Hyun K, Pakosh M, Gallagher R. A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of patient education for secondary prevention in patients with coronary heart disease: impact on psychological outcomes. European journal of cardiovascular nursing. 2022;21(7):643-54.

41. Guo L, Gao W, Wang T, Shan X. Effects of empowerment education on patients after percutaneous coronary intervention: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. 2023;102(23):e33992.

42. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D, Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. European heart journal. 2020;41(3):407-77.

43. Nakano S, Kohsaka S, Chikamori T, Fukushima K, Kobayashi Y, Kozuma K, et al. JCS 2022 Guideline Focused Update on Diagnosis and Treatment in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation Journal. 2022;86(5):882-915.

44. Hoffmann U, Ferencik M, Udelson JE, Picard MH, Truong QA, Patel MR, et al. Prognostic Value of Noninvasive Cardiovascular Testing in Patients With Stable Chest Pain: Insights From the PROMISE Trial (Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain). Circulation. 2017;135(24):2320-32.

45. Bettencourt N, Mendes L, Fontes JP, Matos P, Ferreira C, Botelho A, et al. Consensus document on chronic coronary syndrome assessment and risk stratification in Portugal: A position paper statement from the [Portuguese Society of Cardiology’s] Working Groups on Nuclear Cardiology, Magnetic Resonance and Cardiac Computed Tomography, Echocardiography, and Exercise Physiology and Cardiac Rehabilitation. Revista portuguesa de cardiologia : orgao oficial da Sociedade Portuguesa de Cardiologia = Portuguese journal of cardiology : an official journal of the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. 2022;41(3):241-51.

46. Knuuti J, Ballo H, Juarez-Orozco LE, Saraste A, Kolh P, Rutjes AWS, et al. The performance of non-invasive tests to rule-in and rule-out significant coronary artery stenosis in patients with stable angina: a meta-analysis focused on post-test disease probability. European heart journal. 2018;39(35):3322-30.

47. Shaw LJ, Peterson ED, Shaw LK, Kesler KL, DeLong ER, Harrell FE, Jr., et al. Use of a prognostic treadmill score in identifying diagnostic coronary disease subgroups. Circulation. 1998;98(16):1622-30.

48. Matta M, Harb SC, Cremer P, Hachamovitch R, Ayoub C. Stress testing and noninvasive coronary imaging: What’s the best test for my patient? Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2021;88(9):502-15.

49. Fowler-Brown A, Pignone M, Pletcher M, Tice JA, Sutton SF, Lohr KN. Exercise tolerance testing to screen for coronary heart disease: a systematic review for the technical support for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of internal medicine. 2004;140(7):W9-24.

50. Sun Y, Li W, Yin L, Wei L, Wang Y. Diagnostic accuracy of treadmill exercise tests among Chinese women with coronary artery diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of cardiology. 2017;227:894-900.

51. Banerjee A, Newman DR, Van den Bruel A, Heneghan C. Diagnostic accuracy of exercise stress testing for coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. International journal of clinical practice. 2012;66(5):477-92.

52. Yao SS, Bangalore S, Chaudhry FA. Prognostic implications of stress echocardiography and impact on patient outcomes: an effective gatekeeper for coronary angiography and revascularization. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2010;23(8):832-9.

53. Chaowalit N, Arruda AL, McCully RB, Bailey KR, Pellikka PA. Dobutamine stress echocardiography in patients with diabetes mellitus: enhanced prognostic prediction using a simple risk score. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006;47(5):1029-36.

54. Chuah S-C, Pellikka PA, Roger VL, McCully RB, Seward JB. Role of Dobutamine Stress Echocardiography in Predicting Outcome in 860 Patients With Known or Suspected Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 1998;97(15):1474-80.

55. Sicari R, Pasanisi E, Venneri L, Landi P, Cortigiani L, Picano E. Stress echo results predict mortality: a large-scale multicenter prospective international study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;41(4):589-95.

56. Kumar A, Doshi R, Khan SU, Shariff M, Baby J, Majmundar M, et al. Revascularization or Optimal Medical Therapy for Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: A Bayesian Meta-Analysis of Contemporary Trials. Cardiovascular revascularization medicine : including molecular interventions. 2022;40:42-7.

57. Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, Cohen I, Berman DS. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107(23):2900-7.

58. Abidov A, Bax JJ, Hayes SW, Cohen I, Nishina H, Yoda S, et al. Integration of automatically measured transient ischemic dilation ratio into interpretation of adenosine stress myocardial perfusion SPECT for detection of severe and extensive CAD. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2004;45(12):1999-2007.

59. Hachamovitch R, Kang X, Amanullah AM, Abidov A, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, et al. Prognostic implications of myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography in the elderly. Circulation. 2009;120(22):2197-206.

60. Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, Hartigan PM, Maron DJ, Kostuk WJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356(15):1503-16.

61. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Bangalore S, O’Brien SM, Boden WE, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2020;382(15):1395-407.

62. Ricci F, Khanji MY, Bisaccia G, Cipriani A, Di Cesare A, Ceriello L, et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Stress Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients With Known or Suspected Coronary Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA cardiology. 2023;8(7):662-73.

63. Vincenti G, Masci PG, Monney P, Rutz T, Hugelshofer S, Gaxherri M, et al. Stress Perfusion CMR in Patients With Known and Suspected CAD: Prognostic Value and Optimal Ischemic Threshold for Revascularization. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2017;10(5):526-37.

64. Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Picard MH, Friedrich MG, Kwong RY, Stone GW, et al. Comparative Definitions for Moderate-Severe Ischemia in Stress Nuclear, Echocardiography, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;7(6):593-604.

65. Cury RC, Leipsic J, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Berman D, Bittencourt M, et al. CAD-RADS™ 2.0 – 2022 Coronary Artery Disease-Reporting and Data System: An Expert Consensus Document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the North America Society of Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). Journal of cardiovascular computed tomography. 2022;16(6):536-57.

66. Ahmadzadeh K, Roshdi Dizaji S, Kiah M, Rashid M, Miri R, Yousefifard M. The value of Coronary Artery Disease – Reporting and Data System (CAD-RADS) in Outcome Prediction of CAD Patients; a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Archives of academic emergency medicine. 2023;11(1):e45.

67. Iaconelli A, Pellicori P, Dolce P, Busti M, Ruggio A, Aspromonte N, et al. Coronary revascularization for heart failure with coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. European journal of heart failure. 2023;25(7):1094-104.

68. Taglieri N, Bacchi Reggiani ML, Ghetti G, Saia F, Dall’Ara G, Gallo P, et al. Risk of Stroke in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention versus Optimal Medical Therapy: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0158769.

69. Davari M, Sorato MM, Fatemi B, Rezaei S, Sanei H. Medical therapy versus percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft in stable coronary artery disease; a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. ARYA atherosclerosis. 2022;18(3):1-12.

70. Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, Kanade P, Chandra N, Shaw RE, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circulation Cardiovascular interventions. 2012;5(4):476-90.

71. Folland ED, Hartigan PM, Parisi AF. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy for stable angina pectoris: outcomes for patients with double-vessel versus single-vessel coronary artery disease in a Veterans Affairs Cooperative randomized trial. Veterans Affairs ACME InvestigatorS. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;29(7):1505-11.

72. Hartigan PM, Giacomini JC, Folland ED, Parisi AF. Two- to three-year follow-up of patients with single-vessel coronary artery disease randomized to PTCA or medical therapy (results of a VA cooperative study). Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program ACME Investigators. Angioplasty Compared to Medicine. The American journal of cardiology. 1998;82(12):1445-50.

73. Hueb W, Lopes NH, Gersh BJ, Soares P, Machado LA, Jatene FB, et al. Five-year follow-up of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS II): a randomized controlled clinical trial of 3 therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2007;115(9):1082-9.

74. Lopez-Sendon JL, Cyr DD, Mark DB, Bangalore S, Huang Z, White HD, et al. Effects of initial invasive vs. initial conservative treatment strategies on recurrent and total cardiovascular events in the ISCHEMIA trial. European heart journal. 2022;43(2):148-9.

75. Rezende PC, Hueb W, Garzillo CL, Lima EG, Hueb AC, Ramires JA, et al. Ten-year outcomes of patients randomized to surgery, angioplasty, or medical treatment for stable multivessel coronary disease: effect of age in the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study II trial. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2013;146(5):1105-12.

76. American Heart Association. Life’s Essential 8: Your checklist for lifelong good health [Internet]. Dallas: American Heart Association.

77. Bruyne BD, Pijls NHJ, Kalesan B, Barbato E, Tonino PAL, Piroth Z, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve–Guided PCI versus Medical Therapy in Stable Coronary Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(11):991-1001.

78. Lairikyengbam SK, Davies AG. Interpreting exercise treadmill tests needs scoring system. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2002;325(7361):443.

79. Yao SS, Qureshi E, Sherrid MV, Chaudhry FA. Practical applications in stress echocardiography: risk stratification and prognosis in patients with known or suspected ischemic heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003;42(6):1084-90.

80. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. Recent-onset chest pain of suspected cardiac origin: assessment and diagnosis. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

Copyright © NICE 2020.; 2016.

81. Kattus AA, Alvaro AB, Zohman LR, Coulson AH. Comparison of placebo, nitroglycerin, and isosorbide dinitrate for effectiveness of relief of angina and duration of action. Chest. 1979;75(1):17-23.

82. Aronow WS, Chesluk HM. Sublingual isosorbide dinitrate therapy versus sublingual acebo in angina pectoris. Circulation. 1970;41(5):869-74.

83. Mangione NJ, Glasser SP. Phenomenon of nitrate tolerance. American Heart Journal. 1994;128(1):137-46.

84. AHFS Drug Information 2017. McEvoy GK, ed. Propranolol. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2017.

85. Murdoch D, Heel RC. Amlodipine. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use in cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 1991;41(3):478-505.

86. AHFS drug information 2017. McEvoy GK, ed. Nitrates and Nitrites General Statement. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2017.

87. Shu de F, Dong BR, Lin XF, Wu TX, Liu GJ. Long-term beta blockers for stable angina: systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2012;19(3):330-41.

88. Belsey J, Savelieva I, Mugelli A, Camm AJ. Relative efficacy of antianginal drugs used as add-on therapy in patients with stable angina: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2015;22(7):837-48.

89. Turgeon RD, Pearson GJ, Graham MM. Pharmacologic Treatment of Patients With Myocardial Ischemia With No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. The American journal of cardiology. 2018;121(7):888-95.

90. Morse JR, Nesto RW. Double-blind crossover comparison of the antianginal effects of nifedipine and isosorbide dinitrate in patients with exertional angina receiving propranolol. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1985;6(6):1395-401.

91. Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Spencer FA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI. Antiplatelet drugs: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e89S-e119S.

92. Lewis HD, Jr., Davis JW, Archibald DG, Steinke WE, Smitherman TC, Doherty JE, 3rd, et al. Protective effects of aspirin against acute myocardial infarction and death in men with unstable angina. Results of a Veterans Administration Cooperative Study. The New England journal of medicine. 1983;309(7):396-403.

93. Snow V, Barry P, Fihn SD, Gibbons RJ, Owens DK, Williams SV, et al. Primary care management of chronic stable angina and asymptomatic suspected or known coronary artery disease: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2004;141(7):562-7.

94. Juul-Möller S, Edvardsson N, Jahnmatz B, Rosén A, Sørensen S, Omblus R. Double-blind trial of aspirin in primary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with stable chronic angina pectoris. The Swedish Angina Pectoris Aspirin Trial (SAPAT) Group. Lancet (London, England). 1992;340(8833):1421-5.

95. Ridker PM, Manson JE, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Low-dose aspirin therapy for chronic stable angina. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1991;114(10):835-9.

96. National Clinical Guideline C. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Clinical Guidelines. MI – Secondary Prevention: Secondary Prevention in Primary and Secondary Care for Patients Following a Myocardial Infarction: Partial Update of NICE CG48. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK)

Copyright © 2013, National Clinical Guideline Centre.; 2013.

97. Bangalore S, Fakheri R, Wandel S, Toklu B, Wandel J, Messerli FH. Renin angiotensin system inhibitors for patients with stable coronary artery disease without heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;356:j4.

98. Ong HT, Ong LM, Ho JJ. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEIs) and Angiotensin-Receptor Blockers (ARBs) in Patients at High Risk of Cardiovascular Events: A Meta-Analysis of 10 Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trials. ISRN cardiology. 2013;2013:478597.

99. Michelsen MM, Rask AB, Suhrs E, Raft KF, Høst N, Prescott E. Effect of ACE-inhibition on coronary microvascular function and symptoms in normotensive women with microvascular angina: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. PloS one. 2018;13(6):e0196962.

100. Mills EJ, Wu P, Chong G, Ghement I, Singh S, Akl EA, et al. Efficacy and safety of statin treatment for cardiovascular disease: a network meta-analysis of 170,255 patients from 76 randomized trials. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2011;104(2):109-24.

101. Naci H, Brugts JJ, Fleurence R, Tsoi B, Toor H, Ades AE. Comparative benefits of statins in the primary and secondary prevention of major coronary events and all-cause mortality: a network meta-analysis of placebo-controlled and active-comparator trials. European journal of preventive cardiology. 2013;20(4):641-57.

102. Lu Y, Cheng Z, Zhao Y, Chang X, Chan C, Bai Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of long-term treatment with statins for coronary heart disease: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2016;254:215-27.

103. Pedersen TR, Berg K, Cook TJ, Faergeman O, Haghfelt T, Kjekshus J, et al. Safety and tolerability of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin during 5 years in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Archives of internal medicine. 1996;156(18):2085-92.

104. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet (London, England). 1994;344(8934):1383-9.

105. Athyros VG, Papageorgiou AA, Mercouris BR, Athyrou VV, Symeonidis AN, Basayannis EO, et al. Treatment with atorvastatin to the National Cholesterol Educational Program goal versus ‘usual’ care in secondary coronary heart disease prevention. The GREek Atorvastatin and Coronary-heart-disease Evaluation (GREACE) study. Current medical research and opinion. 2002;18(4):220-8.

106. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)

Copyright © NICE 2023.; 2023.

107. Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(24):3168-209.

108. Salachas A, Papadopoulos C, Sakadamis G, Styliadis J, Voudris V, Oakley D, et al. Effects of a low-dose fish oil concentrate on angina, exercise tolerance time, serum triglycerides, and platelet function. Angiology. 1994;45(12):1023-31.

109. Wu G, Ji Q, Huang H, Zhu X. The efficacy of fish oil in preventing coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2021;100(37):e27253.

110. Cartlidge T, Kovacevic M, Navarese EP, Werner G, Kunadian V. Role of percutaneous coronary intervention in the modern-day management of chronic coronary syndrome. Heart. 2023;109(19):1429-35.

111. Aroesty JM. Patient education: Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (Beyond the Basics) – UpToDate [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 18].

112. Popova NV, Popov VA, Revishvili AS. Coronary Revascularization in Stable Coronary Artery Disease. State of the Art. J Updates Cardiovasc Med. 2023;11(4):127-138. doi:10.32596/ejcm.galenos.2024.2023-6-19.

113. Thiele H, Neumann-Schniedewind P, Jacobs S, Boudriot E, Walther T, Mohr FW, et al. Randomized comparison of minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass surgery versus sirolimus-eluting stenting in isolated proximal left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2009;53(25):2324-31.

114. Blazek S, Rossbach C, Borger MA, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, et al. Comparison of sirolimus-eluting stenting with minimally invasive bypass surgery for stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery: 7-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JACC Cardiovascular interventions. 2015;8(1 Pt A):30-8.

115. Hong SJ, Lim DS, Seo HS, Kim YH, Shim WJ, Park CG, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stent implantation vs. minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass (MIDCAB) in patients with left anterior descending coronary artery stenosis. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2005;64(1):75-81.

116. Park DW, Ahn JM, Park H, Yun SC, Kang DY, Lee PH, et al. Ten-Year Outcomes After Drug-Eluting Stents Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting for Left Main Coronary Disease: Extended Follow-Up of the PRECOMBAT Trial. Circulation. 2020;141(18):1437-46.

117. Kapur A, Hall RJ, Malik IS, Qureshi AC, Butts J, de Belder M, et al. Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with coronary artery bypass grafting in diabetic patients. 1-year results of the CARDia (Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes) trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55(5):432-40.

118. Milojevic M, Serruys PW, Sabik JF, 3rd, Kandzari DE, Schampaert E, van Boven AJ, et al. Bypass Surgery or Stenting for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73(13):1616-28.

119. Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, Siami FS, Dangas G, Mack M, et al. Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(25):2375-84.

120. Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Morice MC, Banning AP, Serruys PW, Mohr FW, et al. Treatment of complex coronary artery disease in patients with diabetes: 5-year results comparing outcomes of bypass surgery and percutaneous coronary intervention in the SYNTAX trial. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2013;43(5):1006-13.

121. Kamalesh M, Sharp TG, Tang XC, Shunk K, Ward HB, Walsh J, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary bypass surgery in United States veterans with diabetes. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61(8):808-16.

122. Mohr FW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Feldman TE, Ståhle E, Colombo A, et al. Coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with three-vessel disease and left main coronary disease: 5-year follow-up of the randomised, clinical SYNTAX trial. Lancet (London, England). 2013;381(9867):629-38.

123. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, Jain A, Sopko G, Marchenko A, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(17):1607-16.

124. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, Al-Khalidi HR, Hill JA, Panza JA, et al. Coronary-Artery Bypass Surgery in Patients with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2016;374(16):1511-20.

125. Perera D, Clayton T, O’Kane PD, Greenwood JP, Weerackody R, Ryan M, et al. Percutaneous Revascularization for Ischemic Left Ventricular Dysfunction. The New England journal of medicine. 2022;387(15):1351-60.

126. O’Brien SM, Feng L, He X, Xian Y, Jacobs JP, Badhwar V, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2018 Adult Cardiac Surgery Risk Models: Part 2-Statistical Methods and Results. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018;105(5):1419-28.

127. Shahian DM, Jacobs JP, Badhwar V, Kurlansky PA, Furnary AP, Cleveland JC, Jr., et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons 2018 Adult Cardiac Surgery Risk Models: Part 1-Background, Design Considerations, and Model Development. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018;105(5):1411-8.

128. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145(3):e4-e17.

129. Sianos G, Morel MA, Kappetein AP, Morice MC, Colombo A, Dawkins K, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention : journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2005;1(2):219-27.

130. Byrne RA, Fremes S, Capodanno D, Czerny M, Doenst T, Emberson JR, et al. 2022 Joint ESC/EACTS review of the 2018 guideline recommendations on the revascularization of left main coronary artery disease in patients at low surgical risk and anatomy suitable for PCI or CABG. European heart journal. 2023;44(41):4310-20.

131. De Filippo O, Di Franco A, Boretto P, Bruno F, Cusenza V, Desalvo P, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery surgery for left main disease according to lesion site: A meta-analysis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2023;166(1):120-32.e11.

132. Dimagli A, Soletti G, Jr., Harik L, Perezgrovas Olaria R, Cancelli G, An KR, et al. Angiographic Outcomes for Arterial and Venous Conduits Used in CABG. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023;12(5).

133. Kipp R, Lehman J, Israel J, Edwards N, Becker T, Raval AN. Patient preferences for coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous intervention in multivessel coronary artery disease. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2013;82(2):212-8.

134. Whitney SN, McGuire AL, McCullough LB. A typology of shared decision making, informed consent, and simple consent. Annals of internal medicine. 2004;140(1):54-9.

135. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2015;351:h5000.

136. Thomas RJ, Balady G, Banka G, Beckie TM, Chiu J, Gokak S, et al. 2018 ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2018;11(4):e000037.

Si tienes comentarios sobre el contenido de las guías de práctica clínica, puedes comunicarte con IETSI-EsSalud enviando un correo: gpcdireccion.ietsi@essalud.gob.pe

SUGERENCIAS

Si has encontrado un error en esta página web o tienes alguna sugerencia para su mejora, puedes comunicarte con EviSalud enviando un correo a evisalud@gmail.com